>> The Friday Review: The Losers: Ante Up

>> The Friday Review: Marvels

More...

Howard Chaykin once had this to say about Chris Claremont: "Comics, as they are today, owe everything they've got to [his work]. He invented the contemporary language of comics."

Read that again. Comics owe everything (emphasis mine) to Claremont. That's a hell of a grandiose statement.

Now, here's Doug Petrie, staff writer on BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER: "Growing up, I was an enormous fan of Marvel Comics ... when John Byrne and Chris Claremont took over X-MEN, I was just addicted to it. Everything Marvel Comics did, from 1975 [onwards], I absorbed completely..."

Even if I weren't a fan of the show, the BUFFY/X-MEN parallels would be fairly obvious. Despite its post-modern horror-film trappings, BUFFY - much like the Claremont/Byrne X-MEN - is adolescent soap opera. Many of the ways the characters are delineated tend to be similar: Giles is essentially Professor X, Spike fulfils the Wolverine role, and so on.

There was one instance, though, that brought this right to the fore: the closing episodes of the sixth season, whereupon shy witch Willow, mad with grief, goes on a magic-fuelled rampage.

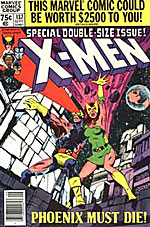

The suggestion was made in the dialogue that Willow had gone 'Dark Phoenix'; with such an overt reference to what many consider to be the high point of the Claremont/Byrne run, it appeared that credit was given where it was due. (Somewhat ironic, considering that Claremont's successors on the X-MEN, Fabian Nicieza and Scott Lobdell, would go on to work on the BUFFY comic book; what's that they say about a photocopy of a photocopy?)

The suggestion was made in the dialogue that Willow had gone 'Dark Phoenix'; with such an overt reference to what many consider to be the high point of the Claremont/Byrne run, it appeared that credit was given where it was due. (Somewhat ironic, considering that Claremont's successors on the X-MEN, Fabian Nicieza and Scott Lobdell, would go on to work on the BUFFY comic book; what's that they say about a photocopy of a photocopy?)

Which begs the question: is the Claremont/Byrne X-MEN really worth the high regard many place it in?

Claremont described his approach to the X-MEN this way: "Passion always comes before logic. You can always paste in logic. But the reader must first care about the characters."

In this regard, Claremont succeeded Stan Lee as the comic book writer at the end of the 70's. Constant novelty, florid emotionalism, reader identification; the notions and concepts Marvel made their own were taken to their utmost limit by Claremont and Byrne.

In fact, according to Howard Chaykin, it appeared to be something of a natural (if unwanted) progression: "[A]fter Stan Lee came along, all these guys who'd grown up on the stuff ... took it seriously. Now the guys producing comic books really think it's art..."

Much of Marvel's output during the 70s bore this out: from Thomas, Conway and Englehart, to MacGregor, Gerber and Starlin, comics - long seen as disposable entertainment - were treated as High Art. With Len Wein and Dave Cockrum redeveloping the X-Men in the midst of this, the situation was ripe for Claremont and his artists to put passion before logic, and thus capture the attention of fandom.

The way Claremont put it in an interview circa 1988, it sounds as if he was looking to create addicts. "As a writer and as a reader, this is what I look for, in my own work, and in someone else's - you get to the end [of the story, and ask] 'What happens next?' That is our function ... as storytellers, as entertainers - we want the audience coming back for more ... I want kids lined up outside comic book stores ... waiting for the next [issue of] X-MEN, which is how it used to be back when John and I were doing it."

The way Claremont put it in an interview circa 1988, it sounds as if he was looking to create addicts. "As a writer and as a reader, this is what I look for, in my own work, and in someone else's - you get to the end [of the story, and ask] 'What happens next?' That is our function ... as storytellers, as entertainers - we want the audience coming back for more ... I want kids lined up outside comic book stores ... waiting for the next [issue of] X-MEN, which is how it used to be back when John and I were doing it."

Claremont continued: "You don't want the readership - crass, callow, manipulative as it sounds ... the option of looking somewhere else. What you want to do is force their eyes ... you want the kid to go to you first. Let him go to the others, but he goes to you first."

It's relatively easy to see why fans of the day took to the Claremont/Byrne X-MEN like they did. There's a great deal of passion, but logic is - by and large - stretched to breaking point, like a condom fitted over a fire hydrant. All the derring-do and high adventure serves to highlight the emotional acrobatics Claremont forces his characters to undergo. He piles on one development after another, until the plot is groaning under the weight of each X-Man's personal turmoil. They agonise and moan and make speeches and ponder the meaning of life: THIS LIFE in spandex.

I'm going to throw some story beats at you. See if you can keep up:

- Shi'ar agent Eric The Red restores Magneto to adulthood with a wave of his hand. Just because he could.

- Firelord happens along for no apparent reason other than to throw a tantrum and get whipped by Phoenix.

- Mesmero - a mutant hypnotist, lest we forget - manages to ensnare the X-men into becoming sideshow freaks. Off-panel, no less.

- In the wake of a showdown with Magneto, the X-Men are separated into two groups, each believing the other dead. This plotline drags on for months! (The worst bit is watching Cyclops trying to mourn Jean, and finding he can't, for the sake of group morale. Ah, bless.)

- As a result, some of the group end up in the Savage Land, tangling with Ka-Zar and Sauron for no real reason (other than they were there, I guess), and get involved in another adventure that goes nowhere.- Once back in the US (by way of Japan and Canada), they are promptly captured by Arcade, and waste an issue and a half trying to break out of Murderworld.

- Finally, the much-ballyhooed 'Dark Phoenix Saga' - even in the wake of being undercut by retroactive continuity - doesn't really add up to much. It is clunky, overwritten, and a prime example of Claremont's 'passion before logic' approach. ('Days of Future Past' follows much in the same regard.)

Admittedly, there are some sequences of note during the Claremont/Byrne run: the Moses Magnum/Sunfire story makes good use of the 'family dynamic' inter-relationships between the team members. Also, the Proteus arc is actually quite good, a compact and tight thriller (despite a horrid cliffhanger halfway through).

But I can't honestly concur with Chaykin's statement that comics owe all that much to Claremont; where does that leave Will Eisner, or 2000AD's alumni, or Los Bros Hernandez, among many others? The X-MEN comics were very much of and for their time. They were fun, energetic, and at times groundbreaking, but not the wellspring of modern comics that some would lead you to believe.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.