|

Comic Book Babylon: The Shape Of Comic Book Reading

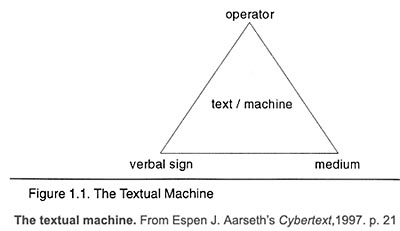

In his translated COLLECTED FICTIONS, Jorge Luis Borges describes his Library of Babel as an endless succession of hexagonal galleries where "each wall of each hexagon is furnished with five bookshelves; each bookshelf holds thirty-two books identical in format; each book contains four hundred ten pages; each page, forty lines; each line, approximately eighty black letters" (113). Each book is unique, even if that individuality differs by only a comma from another near-matching book. It is a literally complete library, with every combination of letters somewhere within it. "All that is able to be expressed, in every language" is there, a catalogue, which "though unimaginably vast, is not infinite" (Borges 115). It is both a fascinating and mind-blowing concept, this Library of Babel - one that is rather awesome even before the subject of pictures and images gets introduced. That is, if Borges' alphabet contained only a pair of characters, there would already be over 2-to-the-millionth-power books. We would already have at least a continent-sized library - even assuming that two walls were open for exiting and entering as Borges dictates - if not a planetary one. But the issue at hand is not mathematics. It is semiotics and the machine known as a "Reader". If, for instance, every one of the library's books each contained a single illustration, how many shelves, walls, and rooms would be needed now? The number jumps immediately from a vast finite amount to the infinite. After all, Borges employed a fictional alphabet with twenty-two characters; including the comma, the period, and the space, he provided over two dozen options for each entry that could, in theory, create any work of any language in the world. Twenty-four markings - and the non-marking of a space - have been isolated and made significant for librarian/readers' use. (Incidentally, it is not worth getting stuck on the fact that "the number of characters required by the American Library Association for bibliographic description of all books contained in American libraries" is actually closer to four dozen (Giral 12). Borges' library is intentionally fantastic, and, for its size, could just as well be based on 49 letters as 22, a number he may have taken from the Cabalah, says Angela Giral. Also, there's a fitting irony for Giral's edition of THE LIBRARY OF BABEL featuring art by Erik Desmazières: Work which is inspired by - but does not follow the actual detailed description of - Borges' Library.) The new question becomes how many different lines, shapes, colours, curves, and shadings a lone illustration would be limited to, and then how many illustrations could possibly be made from those elements. The number, if one does exist, is certainly more than twenty-five; it is more likely that the number is no less than infinity itself. Language can isolate twenty-five markings (or twenty-six or twenty-nine or forty-nine, whichever), but image does not have that luxury. Conversely, words are images, as Scott McCloud, creator of ZOT, likes to note: "Letters are just static images, right? When they're arranged in a deliberate sequence, placed next to each other, we call them words" (8). This makes his overall definition for comic books - "juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to covey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer" - a blurring of the line between Word and Pictures, the Verbal and the Graphical (9). This is especially obvious with a pictographical writing, such as ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, or modern Chinese, where each word is based on a symbol rather than combination of letters. In short, letters of any language are just a fixed number of shapes amongst a limitless number of graphical options. Comic books, "a medium that combines written text and visual art to an extent unparalleled in any other art form," are an excellent battlefield on which to stage this struggle (Abbott 155). And, as such, McCloud is accused of wielding his definition on comics to wipe out the importance or need of words altogether from its essence. Dylan Horrocks, the creator of HICKSVILLE, says McCloud may suffer from a "logophobia" where "comics must not only contain pictorial narrative; they must be dominated by it" or else "the very presence of words - any words - in a comic is a potential threat to its identity as a comic" (36). Lawrence Abbott says as much outright: Members of a comic book audience are called "readers" and not "viewers" because he feels there is "a subordination of the pictorial to the literary in comic art" (156). As a comic book creator himself, Horrocks does not desire for there necessarily to be this clean divide between Words and Images; he concedes that "any borders we may draw along that spectrum are arbitrary and depend more on what relationship we wish to see between words and pictures" (36). Language in a more general sense, as Mario Saraceni points out, is just a "code, or system of signs" for which we can have either "verbal signs and visual signs," one and not the other, or something that is captured by both categories (167). But the distinction, wherever its boundaries may lie, between the two should not be erased or ignored, either. This issue at hand for McCloud, Horrocks, Abbott, Saraceni, and the Library of Babel is a rather widespread one in the study of narrative: the dominance of the verbal sign. While many anthropology books will say that homo erectus writing began as visual signs, modern man favours words - and favours them to a fault. When it comes to books, comics, and even something even marginally associated with verbal signs such as a pie chart, there are "readers", not "viewers". (Similarly, people "talk" online instead of "type"; we "see" a musical, not "hear" one - the dominant channel pervades speech.) Thus, Abbott's claim may be truer than McCloud or Saraceni wish to admit, at least perceptually: Even if pictures tell a thousand of them, words rule. It is not surprising, then, that this bias saturates the structure of narrative theory. After all, most narratology is covered by English and Literature Departments at the university-level, where words are the reigning currency. Still, in his book on the interactive creation of meaning and its relationship to humankind's origins, Wolfgang Iser fashions a model of reading that turns a surprisingly blind eye to visual signs. Though his book, PROSPECTING: FROM READER RESPONSE TO LITERARY ANTHROPOLOGY, both addresses other media like theatre and explores the evolution of literature in human culture, Iser deals only in words. For Iser, meaning is created by a trio of elements. The author's inscrutable intent and choice of expressive medium are only two cogs in the machine that makes meaning. In addition to Author and Text, the Reader completes an interconnected "relationship that is the ongoing process of producing something that did not previously exist" (Iser 249). Through an interplay between the three, not only is a personal understanding of the material created for the reader, but also his or her own unique world. "If we take the result ... to be meaning, then this can only arise of arresting the play-movement that ... will entail decision-making," since each person will have his/her own reaction to any given word based on their personal experience (Iser 252). This is Iser's "way of worldmaking," not unlike the sense one can get when absorbed in a book, lost in one's own world. It also bears a resemblance to Borges' "Universe (which some call the Library)" (Iser 249, Borges 19). So, according to Iser, the Library of Babel could multiply in size for every reader/librarian within it finding his/her own significance for any given book. Unfortunately, both Iser's and Borges' worlds lack pictures of any kind. Another arena besides comics where a more even preference for both verbal and visual sign systems exists would be digital media: computers and the Internet. Here, the language of icons rules side-by-side with words. There are, of course, a number of real-life examples of everyday icons. An octagon can mean "stop" when coloured red; a triangle can mean gay when combined with pink. And a hexagon, for Borges, can represent a near-endless number of books. But only in the abstract world of the desktop does a bomb mean "error", a recycling bin mean "delete", and a simple running man equate to Instant Messaging. The very nature of the Graphic-User Interface (GUI) pioneered by Apple Computers then made a global phenomenon by Microsoft's Windows operating systems makes one equate image with program or function rather than having to utilize lengthy, verbal DOS strings. A program becomes as well known by its icon as its actual name. Sadly, the precocious study of digital media often does little better than literature's narrative theory in bucking the trend. Take, for instance, Espen J Aarseth's CYBERTEXT. One of the key premises to the book is the notion that Western society is full of cyborgs; that is, if we view "texts as a kind of machine" that is one part verbal sign, one part medium, and one part human (Aarseth 55). While Aarseth has a different meaning for "text" than Iser, their trio of points is the same. "Difference between texts can be described in terms of differences along these three dimensions," say Aarseth: "The Textual Machine" composed of "verbal sign", "medium" and "operator" (55, 21).

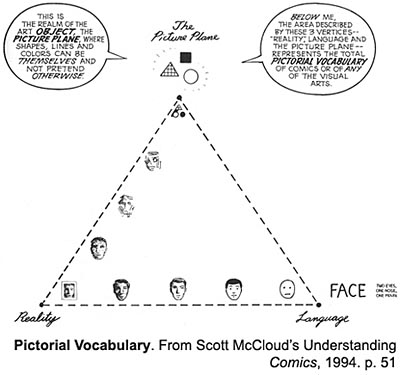

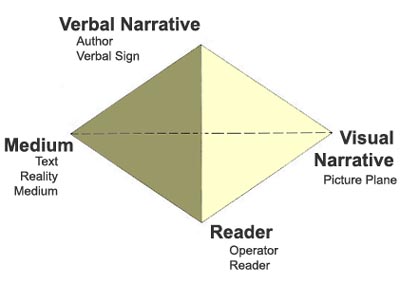

In the same way that Iser's reader plays with a text, Aarseth's operator creates one by entering into a system with words placed in a medium (be it a computer screen, a book page, a billboard, etc). More accurately, that system creates a "cybertext" which is a unique product brought about by the personal meaning gained by a back-and-forth with the verbal sign and medium (1). Unfortunately, for a book that goes so far to explore the semiotic value of images from primitive video games like LEMMINGS, DARK CASTLE, and BRICKLES PLUS, CYBERTEXT remains fairly closed off to actually considering visual signs in creating a text. By definition, "a text, then, is any object with the primary function to relay verbal information" (62, my emphasis). So, to find a narrative "world" model that does include visual signs, the discussion returns to McCloud. In his UNDERSTANDING COMICS, he suggests two directions, two vectors, a comic artist can take their work in. The artist can iconically represent Reality, moving from simple representations of it all the way over to purely verbal symbols, which McCloud flatly calls "Language" (51). Or, the artist can move away both from Reality and its representation towards an abstract "realm of the art object, the Picture Plane, where shapes, lines and colors can be themselves" (51). The three together - Reality, Language, and The Picture Plane - form the triangular area of what McCloud calls an artist's "Pictorial Vocabulary" (51). This is a somewhat confusing term, since "Language" only means verbal signs for McCloud, yet his "vocabulary" is meant to include every sign. He has also made one other oversight: In giving the artist/author a complete toolbox, McCloud omitted the viewer/reader entirely.

All of this gives us not three points by which to shape a two-dimensional, triangular model for eliciting comic book narrative meaning - it gives us four points, taking the model of comic narrative into a third dimension. Iser and Aarseth's models overlap, giving us the initial trio, and then McCloud introduces the fourth, graphical point. Iser and Aarseth both try to explain how the reader/operator is involved in the creation of a text's meaning. McCloud strives to show the full toolbox open to comic book storytellers. Taken all together, this four-point model displays how narrative meaning is constructed in our specific medium. Taking a quick inventory, the four points in question are the Medium, the Reader, the Verbal Narrative, and the Visual Narrative. The first one seems the most straightforward and self-explanatory. The Medium is the tangible comic book itself, the real print product that we purchase. At first glance, it is not a story, not an epic of good versus evil, and not access into another world; it is just a 24-page, stapled paper booklet with a glossy wrap-around cover, generally speaking. Add a Reader to that Medium, and it immediately starts to become something more. Without even one mark on the page, a Reader can find meaning from a presumably blank Medium. A white page, which would generally convey the absence of any story, could mean the eradication of the universe (as it does in DC Comics' ZERO HOUR #0) or a blinding snowstorm (as it does in WHITEOUT). Further, why "reader" and not "operator", "viewer", or even something more broadly cognitive like "interpreter"? This is not a surrender to the dominant verbal sign, as suggested above. Instead, it is an acknowledgement both of the skill involved in deciphering visual signs and that pictures are just as much a language - a sign system - as words. The reader is there to take all of the comics' content and imbue it with meaning. "Verbal Narrative" is not a term that either Iser or Aarseth uses, but arises from this new 4-point tetrahedron model. It captures Iser's "Author", Aarseth's "Verbal Sign", and McCloud's "Language." The last two are easy to combine: What McCloud means as "Language" is not the all-purpose "sign system" term we have been using, but rather "verbal signs" or, simply, words. And, these are not just any, random words. They have been deliberately chosen by the Author, strung into sentences, paragraphs, chapters, and, in total, a story. When holding the tangible product of the Medium, though, the Author is absent - he/she cannot stand over each reader's shoulder and explain what was meant - and the Verbal Narrative becomes the only evidence of his/her existence.

(Even now, there is no solid proof that this essay is anything other than the random selection of words by a computer adhering to English grammatical rules. Like the Library of Babel, this could just be one of a near-infinite number of verbal permutations. While its potential coherence suggests that there is a human Author behind it, only a Reader's personal interpretation of it can truly determine its meaning.) "Narrative" itself is a very flexible yet appropriate term in place of "Sign" on the tetrahedron. The premise, after all, is that these are comic books or graphic novels, implying that, instead of just displaying unconnected random or partial samples of sequential art, some form of story or plot will be told. Even for those series whose plotlines continue monthly and seem never-ending, narrative still very much exists. There are embedded narratives, mirror-texts - to use two terms of narratologist Mieke Bal - and a host of other mid-/stopping-points at which to conclude something still-unfolding as a narrative. In fact, Bal gives the following definition for "narrative":

A narrative text is a text in which an agent relates ('tells') a story in a particular medium, such as language, imagery, sound, buildings or a combination thereof. A story is a fabula that is presented in a certain manner. A fabula is a series of logically and chronologically related events that are caused or experienced by actors. An event is the transition from one state to another state. Actors are agents that perform actions. They are not necessarily human. (5) So, to summarise, a narrative is when someone/something tells, through some medium, of someone/something undergoing a change. "Change" here is being used in the most intentionally vague, encompassing way, since it can be a change in location, shape, opinion, dimension, emotion, etc. And, though Bal is similarly dominated by the verbal sign as Iser and Aarseth were when she says "language," it can be communicated in words, motion, images, or any other communicative medium. A ballet can be a narrative. A hospital chart can be a narrative. A stock market report can be a narrative. Even this essay - where the "actors" are Iser, Aarseth, and McCloud's models that are changing into the tetrahedron - can be a narrative. So, if narrative is so flexible and all-encompassing, why divide it in two to "Verbal Narrative" and "Visual Narrative"? If we solely existed in Borges' all-verbal Library, there would be no reason. That is, if this was a medium where the verbal sign did exclusively dominate, then there would be no "Visual Narrative" point and Iser and Aarseth's models would be correct. However, this is comics, where images are at least half the language. And, true to Bal, pictures can form valid narrative as easily and functionally as words. Mainstream comics have dabbled in this pseudo-pantomime, such as the infamous GI JOE silent issue #24 in 1984, the September 11th tribute stories of MOMENT OF SILENCE, and the even more recent December 2002 company-wide "Nuff Said" event from Marvel Comics. It may be an interesting challenge for some creators, but, generally speaking, it is simply a limitation. But it does at least prove, as if there were any doubt, the viability of visual narrative. In most comics, the visual and the verbal narratives seem to be telling the same story. But, to be technical, it is actually the same fabula - Bal's tricky designation - not the same story. That is, they both present events from the same general plot, to use a more informal term, but not necessarily at the same time and in the same order. The captions may be disclosing a character's inner monologue, for instance, while the panels show that character leaping to safety. Or, as a reverse example, word balloons could be a fight between two off-panel parents while the panel shows a tearful child trying to sleep. It is a dreadfully boring, narrow comic that has the visual and verbal reflect the exact same thing in each and every panel. There would be no point for the replication and, ultimately, no reason for doing this narrative in comic form. Since the visual and the verbal narratives may be telling different parts of the same fabula simultaneously, it stands to reason that there may also be two different narrators for a given panel as well. Take, for instance, an example from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' WATCHMEN, Chapter II "Absent Friends". Over the final pages of this issue, the vigilante Rorschach recounts a joke about the clown Pagliacci in the caption boxes above a series of images from the late Comedian's life. The punchline hits just as the Comedian is thrown out the window. Rorschach says, "Good joke. Everybody laughs. Roll on snare drum," as the Comedian is seen plummeting to the pavement, adding "Curtains" as the panel goes blood red (II.28). Certainly, there is an obvious, fitting irony to both the life of the brutal Comedian being compared to the Pagliacci joke and the alternative meaning for "curtains" as death rather than the close of a show. But Rorschach was present for none of these events in the Comedian's life, particularly his demise, which is the central mystery to the story. It is focalised through a variety of other individuals, including the Comedian's old enemy, Moloch, the Comedian's unknown murderer, and the Comedian himself. Thus, Rorschach may be the verbal narrator for this portion of the issue, but he could not be one of its visual narrators. This distinction becomes particularly important when it is taken advantage of by a savvy creator to create a schism between the two narratives; that is, the visual and verbal narratives may actually be spinning different yarns. Pulitzer Prize-winning comic auteur Art Spiegelman makes excellent use of this technique to emphasize the discord between Holocaust-surviving father and comic book-writing son in MAUS and MAUS II. In his article for THE GRAPHIC NOVEL, Ole Frahm catches one of these moments:

[Art Spiegelman] represents the memories of the witness and by necessity alters them. For example, he corrects them in detail: ... the father does not mention [Doctor] Mengele [in the concentration camps]. He remembers that "Eichman" selected him on two occasions. But the chronicler has consulted other sources and knows that this statement cannot be correct. He thus interferes with the recollections of the witness to provide the correct name of his perpetrator. (67) Despite his father's testimony to the contrary as the verbal narrator, the chronicling son offers a separate, corrected visual narrative of Mengele being present. A second, similar instance takes place just prior to that scene where the survivor-father discusses marching in Auschwitz. At first, an orchestra is portrayed in the background, since his son "read about the camp orchestra that played" (Spiegelman 54). Even once the father corrects him by saying that there were "not any orchestras", the top of the musicians' instruments can still be seen obscured in the background even as the father is verbally denying it; the son's belief in the "well documented" performers visually trump his belief in his father's less reliable, personal memories (54). This sort of narrative duplicity and duality, therefore, can be employed to amplify the themes and messages of the shared fabula. Returning the discussion to WATCHMEN, for instance, Stuart Moulthrop articulates how the "overlapping, tangled, and intersecting narrative lines, including double lives, nefarious plots, stories within stories, and texts within texts" actually suggest a fitting architecture ("Misadventure"). As a near-omnipotent character, Doctor Manhattan perceives existence as a complex jewel rather than a straight, chronological line. He "is frustrated by his wife [Laurie]'s inability to perceive more than a single facet of the 'jewel'...The architecture of the work [WATCHMEN] seems very close to Dr Manhattan's image of time, 'an intricately structured jewel' - though like Laurie we are unable to perceive the design as a whole until the final chapter" (Moulthrop, "Misadventure"). Aarseth, Iser, and even McCloud are in positions similar to Laurie, seeing only "one facet" rather than the full structure before them. By considering comic narrative through this tetrahedron model, we can not only take into better account the functions of both the verbal and visual components to the medium but also highlight the lesser-considered techniques exemplified by Spiegelman and Moore. The tetrahedron adds a new but significant shape for comic books to the halls of Borges' near-endless hexagons.

Works Cited:

A David Lewis is a graduate of Brandeis and Georgetown and an experienced lecturer on comics. With his collaborators at Red Eye Press he works on the comics MORTAL COILS and VALENTINE. Ninth Art endorses the principle of Ideological Freeware. The author permits distribution of this article by private individuals, on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice. Back. |