>> Beyond Borders: Mondo Loco

>> Beyond Borders: Every Picture Tells A Story

More...

Photographs don't have the best press these days inside comics fandom. Just mention photography in relation to comics will earn you some awful looks, and possibly a lecture on the evils of lightboxing, Photoshop and tracers - as if photo referencing weren't an integral part of the comic artist's toolbox. What is photo reference, after all, but the logical evolution of the use of models and painting from life?

I can understand the scoffing about so-called artists who barely apply a couple filters to a glossy magazine cover and send it straight off to his editors, but using a photograph as a framework or reference has always been - and it still is - a legitimate tool for the illustrator.

Hugo Pratt, a master of detail and a genius watercolorist, always photo-referenced hardware for the sake of realism, either because he didn't have the time to paint every scratch and insignia on a tank's hull, or couldn't accurately replicate the puzzling camouflage of a Luftwaffe fighter. The school of 70s Spanish hyperrealists stormed open the gates of American comics thanks to some wonderful works that were allegedly nothing more than painted photo novellas.

What do we prefer? A bit of photo referencing in service to glorious storytelling, or a badly drawn building surrounded by equally badly drawn, non-referenced figure work? There is a huge difference between an artist who is merely lazy and one who chooses to call upon a wide array of tools to create their works, including pencils, computers and cameras.

Why the tirade? Because I am about to introduce you to a work that mixes the comic form with photographs and I don't want to see a single brow rising.

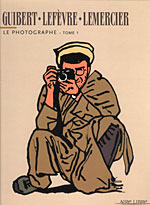

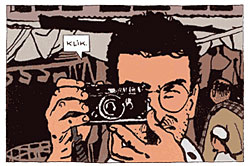

LE PHOTOGRAPHEUR is a strange blend of travel book and comic-book, which mixes photography and drawings - altered, painted over, modelled around, traced, re-imagined, and remixed to such an extent that the line separating photography and illustration not only blurs, but completely disappears. It charmingly combines both arts in one crossover package to present a story - a surprisingly enthralling one for such an experimental work - about a trek through Afghanistan surrounded by the fearsome Mujahedeen. Or, as we know them today, 'those crazy, towel-headed terrorists'.

LE PHOTOGRAPHEUR is a strange blend of travel book and comic-book, which mixes photography and drawings - altered, painted over, modelled around, traced, re-imagined, and remixed to such an extent that the line separating photography and illustration not only blurs, but completely disappears. It charmingly combines both arts in one crossover package to present a story - a surprisingly enthralling one for such an experimental work - about a trek through Afghanistan surrounded by the fearsome Mujahedeen. Or, as we know them today, 'those crazy, towel-headed terrorists'.

Or maybe not. There was a time when bearded, Kalashnikov-carrying Muslims dressed in rags and slippers were a symbol of bravery and selflessness. It was a fabled time when Donald Rumsfeld was able to pay a cordial visit to friendly dictator Saddam Hussein (no relation to today's evil dictator Saddam Hussein), and John Rambo shared tea, Commie-slaughtering jokes and goat-petting advice with Osama Bin Laden while Colonel Trautman grinned and taught ten-year-olds how to flambée Spetznatz until crispy pinko golden.

During the 80s, mujahedeen were trés cool fellas, fighting the good fight against Communism, protecting the capitalistic dream one peshmerga at a time, every day, live on national TV. We were all Osama's bitches back then.

But we couldn't really help it. The Russians didn't have the Hollywood promotional machine the CIA had, ready to downplay the mujahedeen peccadilloes just as America had done with the South Vietnamese administration that they used to fight Victor Charles, the evil Commie 'gook', back in the day. So, helped by Reagan's PR machine, we were sold on the concept that these guys were fighting not for some medieval clothing customs and their right to happily kill each other, as they had been doing over the ages, but to defend the Western way of life. As always, the Hollywood method succeeded, and we bought it all, and even asked for more.

But what exactly happened in Afghanistan during the 80s? Who were this guys who fought heavily armoured tanks armed only with tiny assault rifles and Molotov cocktails? Not all of them are Taliban now, nor were all of them honest-to-God freedom fighters then. This was a time in history when, despite the way it's been portrayed in the movies, we can be certain of very little, because none of us were there. The purpose of this book is basically to tell us what life was like in the shadow of the Hinds. It's one of the few truly eyewitness reports on the Mujahedeen Wars and the Afghan Soviet occupation, because the writer, Didier Lefévre, was actually there.

A volunteer photographer and journalist for Mediciens sans Frontiers, Lefévre travelled to Pakistan in 1986 to join a Soviet-vetoed MSF convoy en route to one of the mujahedeen strongholds in occupied Afghanistan.

A volunteer photographer and journalist for Mediciens sans Frontiers, Lefévre travelled to Pakistan in 1986 to join a Soviet-vetoed MSF convoy en route to one of the mujahedeen strongholds in occupied Afghanistan.

This meant that he had to travel on foot across some of the highest mountains on Earth, under constant threat of Soviet artillery and choppers, to try to bring some medical assistance to the Afghan resistance.

That trip and the countless pictures he took during it are the basis for LE PHOTOGRAPHEUR. Composed of three separate volumes, of which the first two have been released, the story is told in simple instalments and at an almost glacial pace, as if we ourselves were experiencing the trip, and it excels in its naturalism and objectivity. Lefévre doesn't take sides. His job, after all, is to bear witness.

But the credit for LE PHOTOGRAPHEUR doesn't belong solely to Lefévre. What makes it a masterpiece is the involvement of aspiring young gun Emmanuel Guibert. When Lefévre showed Guibert his photos, it probably took the artist all of about three seconds to realise how powerful it would be to use the language of comics to fill in the blanks between the photographs.

Guibert is no stranger to experimentation. His first work, BRUNE, published in 1992 and set during the rise of Nazism in Germany, demonstrated his love for historical comics and showcased his detailed and naturalistic pencils.

Sadly, the book was not a success, and it was not until 1997 that he published again. He then met and began to collaborate with the guys at L'Association - first with Johann Sfar in the delightfully camp and silly LA FILLE DU PROFESSEUR, which won him an Alph´ Art in Angouléme, and later with David B in CAPITAINE ÉCARLATE. In those books, Guibert's art gradually lost detail, gaining heavier inks and stronger shades - a tendency that exploded on his next solo work, LA GUÉRE DE ALAN.

Another critical and public hit, ALAN tells the story of American soldier Alan Ingram Cope, a friend of Guibert's, during the end of World War II. Guibert slowly and carefully details every bit of Cope's story in order to submerge the reader in his life, and to enhance this feeling he used photographs, not simply as photo reference, but as a canvas for the art. Guibert scanned the photos and painted over them, or added to, subtracted from or expanded them, creating the perfect collage, making comics and photography an inseparable whole.

LE PHOTOGRAPHEUR, expands upon this technique to perfection. Guibert not only works over the photographs, but also places them on the pages, creating the perfect marriage of photograph and comic book storytelling, and conjuring up a moving, lifelike, naturalistic portrait of mountain life under the brutal Soviet star. The end result is perhaps the most perfect example of a carnet de voyage ever created.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.