>> The Friday Review: Zero Girl

>> The Friday Review: Ruse: Enter The Detective

More...

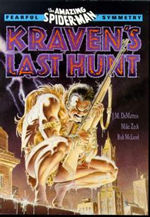

Writer: JM DeMatteis

Writer: JM DeMatteis

Artist: Mike Zeck

Colourists: Mike Zeck, Ina Tetrault

Letterer: Rick Parker

Inker: Bob McLeod

Collecting WEB OF SPIDER-MAN #32-33, AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #293-294, and SPECTACULAR SPIDER-MAN #131-132.

Price: $15.95

Publisher: Marvel Comics

ISBN: 0-87135-691-0

In the world of super-hero comics, the only certain thing is, apparently, taxes. 'Cause death sure as hell isn't. Sure, most comic book heroes have died at one time or another, but they all come back. That inevitable resurrection makes the stories in which our favourite characters die lose much of the emotional punch they might otherwise carry. When Superman dies, we find it hard to care, for we know he'll be back to his old self in no time. Call this lack of emotional gravitas the fundamental rule of comic book death. But, like any rule, it has exceptions. One exception being KRAVEN'S LAST HUNT.

Almost every major character has them; those big stories where they "die". Captain America, by my count, has had at least three. Spider-Man's came in KRAVEN'S LAST HUNT, a six -part tale written by JM DeMatteis and pencilled by Mike Zeck, which wove through six issues of the three main Spider-titles of the day in 1989. And, as in all of these tales (and I'm not really spoiling anything), Spider-Man doesn't really die. Yet for several reasons, this 'death' story stands apart from the crowd.

Spider-Man has a unique status in the comic book world as a high profile, publicly recognised character in the real world who, in the fictional world, is not an idolised and beloved hero, but rather a shadowy and untrustworthy semi- or even anti-hero. This duality allows DeMatteis to play with how Spider-Man's "death" affects those close to him, particularly his wife Mary Jane, rather than focusing on how the rest of the Marvel Universe would take Spider-Man's death, or how it would play on the evening news. At the same time, his story was guaranteed a certain amount of attention, dealing as it does with the "death" of such a major character.

As for the story itself, in simple structural terms it's not too inventive - a traditional Spider-villain goes mad and has a diabolical plan that he must bring to fruition. What gives the story much of its weight is the details. Kraven, the chosen villain, doesn't just go mad, but becomes obsessed with Spider-Man, and his plan involves "killing" Spider-Man, taking his place and proving himself worthy where the real Spider-Man was not, by defeating a villain (Vermin) that Spider-Man could not. Again, it's a private, intimate story, a quality that aids immeasurably in setting the tone.

As for the story itself, in simple structural terms it's not too inventive - a traditional Spider-villain goes mad and has a diabolical plan that he must bring to fruition. What gives the story much of its weight is the details. Kraven, the chosen villain, doesn't just go mad, but becomes obsessed with Spider-Man, and his plan involves "killing" Spider-Man, taking his place and proving himself worthy where the real Spider-Man was not, by defeating a villain (Vermin) that Spider-Man could not. Again, it's a private, intimate story, a quality that aids immeasurably in setting the tone.

One of the best things about the way that DeMatteis handles Spider-Man's "death" is how understated the actual moment is. Think of some other iconic deaths in comic history. Superman dies in a battle so epic as to be ridiculous. The Flash saves an infinite number of universes (and, presumably, an infinite number of people). Green Lantern goes insane and becomes a mass murderer before sacrificing himself to save the world. (Or something like that. Never really followed the Lantern). And Spider-Man? Spider-Man is ... shot. Brooding about his own mortality, a mindset brought upon by the death of Joe Face, a sometime informant, Spider-Man is tagged by Kraven with a tranquilliser dart. Kraven manages to get a net onto a groggy Spider-Man, and then shoots him. It's a wonderful moment simply for being so mundane.

KRAVEN'S LAST HUNT also works because, in many ways, it's not a Spider-Man story. It's Kraven's story, and in his mad obsession to prove himself Spider-Man's superior; first by "killing" him and then by becoming him - donning the black spider suit and patrolling the city - we get a real sense of Kravinov the man. It is Kraven's arc, in the end - not Spider-Man's - that holds the most poignancy. DeMatteis does a fine job here of delineating Kraven's madness. In some rather disturbing scenes we see a frenzied, naked Kraven literally consuming hundreds of spiders and facing off in battle against a hallucinogenic monster spider comprised of millions of the real thing. DeMatteis also makes extensive use of inner monologues, in an almost stream-of-consciousness way. In this manner too we are able to get inside Kraven's head and understand him as more than your typically insane villain.

Mike Zeck nicely compliments the low-key and very ground-level vibe of the book with his realistically detailed pencils. Particularly in his close ups, be it a shot of Vermin (the rat-like villain Kraven must defeat) licking a police officer's face or a dramatic shot of a muddied Spider-Man bursting out of his grave, Zeck's knack for clean, simple detail is well-utilised. The dark colouring, lacking any bright tones, also does a good job of maintaining that feel of a quiet and intimate story. The spider-suit of the time, the black costume, also adds immeasurably to that feel of claustrophobia the story depends on. One is forced to wonder if this story could work at all in the familiar red and blue garb.

Zeck also does a nice job of using spiders and rats as symbols, respectively, of Spider-Man and Vermin. The aforementioned splash of Spider-Man bursting from his grave is given a heightened quality by the dozens of spiders Zeck draws in around the grave itself. And a quiet moment where Vermin is spooked out of surfacing to the streets by a small spider clinging to the edge of a manhole breaks the mostly incessant tension of the book nicely.

Zeck also does a nice job of using spiders and rats as symbols, respectively, of Spider-Man and Vermin. The aforementioned splash of Spider-Man bursting from his grave is given a heightened quality by the dozens of spiders Zeck draws in around the grave itself. And a quiet moment where Vermin is spooked out of surfacing to the streets by a small spider clinging to the edge of a manhole breaks the mostly incessant tension of the book nicely.

Zeck and DeMatteis also do a wonderful job of portraying Parker's mind as he lays buried beneath the earth. A great use of white space and, again, the symbol of the spider and the use of interior monologue, give us a dreamlike accounting of Spider-Man's death. This, added to the understated nature of his death - no public mourning, no grand battle - makes his eventual resurrection, and reunion with new bride Mary Jane, quite moving.

KRAVEN'S LAST HUNT is one of those stories that I continually find myself returning to (especially after an event like this summer's OUR WORLDS AT WAR over at DC, where death is used, artificially and unconvincingly, to evoke some of the emotions of a real war). And when I do return to it, it is those small moments I find myself admiring all over again. DeMatteis's effective transcribing of the Blake poem that begins "Tyger, Tyger, burning bright" to "Spyder, spyder, burning bright." A scared and alone Mary Jane killing a rat with a shoe. The subtle way that Zeck differentiates the bulkier Kraven underneath the black spider-suit, and the way that he makes it clear, through body positions and the way he moves, that this is not the real Spider-Man. But, most of all, it's that moment when Kraven pulls the trigger and neither Spider-Man nor, after all these years, the reader, can truly believe it. These are the reasons why this story stands apart.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.