>> The Friday Review: The Losers: Ante Up

>> The Friday Review: Marvels

More...

Writer: Frank Miller

Writer: Frank Miller

Artist: Bill Sienkiewicz

Letterers: Jim Novak and Gaspar Saladino

Collects ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN #1-8

Price: $24.95

Publisher: Marvel

ISBN: 0871353091

I'm of the opinion that Frank Miller very much likes taking the piss.

For example: look at BATMAN: THE DARK KNIGHT STRIKES AGAIN (however laboured its points were), GIVE ME LIBERTY, even those two ROBOCOP films he wrote; each had an underlying current of pointed socio-political satire. Hell, even something as throwaway as that BATMAN/SPAWN crossover had its fair share.

On the other hand, something along the lines of ELEKTRA LIVES AGAIN or several of Miller's SIN CITY projects takes the proverbial Mickey in another way: out of the readers. (THE DARK KNIGHT STRIKES AGAIN also being an odious culprit in this regard.) Maybe it's just me, but I sense that Miller knows he can write and/or draw almost anything and readers will lap it up. Hey, if he can get away with it, more power to him.

I find that ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN falls somewhere between those two stools; very much a case of six of one, a half dozen of the other.

The bare bones of the plot is this: Elektra, along with rogue SHIELD agent John Garrett, intend to stop US President potentate Ken Wind from ascending to the Oval Office; to fail means nuclear winter at Wind's hands, as Wind is the human aspect of a demonic creature referred to as 'the Beast'. I grant you, there's more to it than that, but ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN doesn't entirely exist as a narrative in the traditional sense.

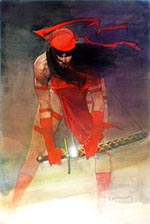

What Miller and artist Bill Sienkiewicz have concocted here is closer to a recollection of a fever-dream or acid flashback. The terse, staccato rhythm of Miller's prose and dialogue interplays with the extreme pallet Sienkiewicz employs, engendering the events related with a surrealistic quality, while maintaining a sense of explicitness (sometimes too detailed for comfort). Despite the feeling of obfuscation, it becomes clear that Miller and Sienkiewicz are working with decided intent (even if it's towards a simplistic declaration: Don't Trust Politicians).

What Miller and artist Bill Sienkiewicz have concocted here is closer to a recollection of a fever-dream or acid flashback. The terse, staccato rhythm of Miller's prose and dialogue interplays with the extreme pallet Sienkiewicz employs, engendering the events related with a surrealistic quality, while maintaining a sense of explicitness (sometimes too detailed for comfort). Despite the feeling of obfuscation, it becomes clear that Miller and Sienkiewicz are working with decided intent (even if it's towards a simplistic declaration: Don't Trust Politicians).

None of the characters are sympathetic, especially not our 'heroes', Elektra and Garrett. And yet, in Miller's deft hands, a hindrance is transmuted into an advantage. With our protagonists being somewhat morally deficient, Wind and his pawns come across as far more reprehensible; ergo, you end up rooting for the 'bad guys' to take out the 'worse guys'. Much of the story's subtext turns upon such ironic switching of the norm: SHIELD agent Chastity McBryde looks like a Playboy centrefold, and yet espouses clean language, even dressing as a nun at one point to fulfil her mission. A heavily armed nun, at that.

ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN is Miller in rapid-fire infodump mode; events are not so much related to the reader as they are lined up and shot out of one of Nick Fury's exaggerated too-big guns. The first chapter is exemplary per Miller's methodology: he doesn't draw the reader into the story, he dumps you into Elektra's psychosis-addled childhood recollections, leaving you to fit the pieces together into some semblance of sense. By the time Garrett is introduced, all testosterone and macho bluster, events begin to fall into some sort of linear fashion - akin to the reader coming down from a drug high.

Thankfully, one doesn't need in-depth knowledge of DAREDEVIL to get satisfaction from this: ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN is a flashback story (which implies the mood evoked by Miller and Sienkiewicz may well have been intentional). Being self-contained is a definite plus, as well - with there being a beginning, middle and end (however open-ended), one doesn't need to worry about 'what happens next', which is a drawback common to much serial fiction. Indeed, if you are au fait with DAREDEVIL continuity, you know what the future has in store for Elektra, which makes events herein somewhat tragic.

Thankfully, one doesn't need in-depth knowledge of DAREDEVIL to get satisfaction from this: ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN is a flashback story (which implies the mood evoked by Miller and Sienkiewicz may well have been intentional). Being self-contained is a definite plus, as well - with there being a beginning, middle and end (however open-ended), one doesn't need to worry about 'what happens next', which is a drawback common to much serial fiction. Indeed, if you are au fait with DAREDEVIL continuity, you know what the future has in store for Elektra, which makes events herein somewhat tragic.

There is somewhat of a flaw in Miller's work here, though: the characterisation of Elektra herself. She comes across as being a blank slate for others to projects their wants and needs onto; other than the aforementioned first chapter, we get very little sense of how she actually feels about the events she finds herself in. Which, again, may be part of Miller's intention, but there's very little empathy to be had on her part. Garrett, on the other hand, is quite likeable for a sociopath, and is very much there for the reader's identification.

ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN is widely seen as Sienkiewicz's tour de force, and with good reason: with his melding of Ralph Steadman's anarchic linework and Chuck Jones' expressionism, bold strides are made in the artistic realm. That's not to say that it's all portraiture and landscapes; Sienkiewicz tells the story while managing not to allow his art to overwhelm Miller's objective. Through varied use of hues and styles, Sienkiewicz leads the reader with one hand while pushing him along with the other. For the art alone, this is worth reading.

However, while ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN does try to say a lot, I'm not convinced it says at as well as it could. It's very pretty to look at, but the political commentary - while valid - comes across as dated, and has '1986' stamped all over it. For all its influence (hello, Joe Casey; step up, Simon Bisley), ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN - though a decent enough read - is unfortunately a curio of a simpler time.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.