>> The Book Review: The Horde

>> What About Bob? An interview with Bob Schreck, Part Two

More...

The author Margaret Atwood once wrote that wanting to meet a writer because you like their book is like wanting to meet a duck because you enjoy pate. Even so, the work of the late Will Eisner left a very strong impression of the man. I would like to have met Will Eisner.

We live in a culture that doesn't often encourage or support its older artists, but what was extraordinary about Eisner was how brilliant his later work was. His name will always be mentioned in the same breath as THE SPIRIT, but reading A FAMILY MATTER or FAGIN THE JEW, one is struck by how vibrant and exciting his later work was. The passion was always there on the page. While no longer technically innovative, he never lost the vitality in his linework, or his skill for telling stories.

Eisner wasn't just another comics artist. Even with THE SPIRIT, he wasn't preoccupied with car chases, fistfights and action sequences. He was interested in stories about people and the city itself. Eisner was at heart a humanist, and approached all his characters as individuals, and he used the medium as best he could to tell their stories. The character of the Spirit was just a vehicle for telling those stories.

"I had been producing comic books for 15-year-old cretins from Kansas," he told The Associated Press in a 1998 interview. With THE SPIRIT, he was aiming for "a 55-year-old who had his wallet stolen on the subway. You can't talk about heartbreak to a kid".

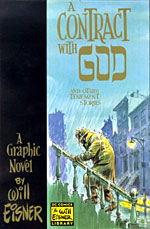

After retiring THE SPIRIT, he largely abandoned comics for design work until the 70s, much of his work ignored even while his techniques became part of the language of comics. The generation of underground cartoonists who emerged in the sixties and seventies had absorbed the vocabulary that Eisner helped to develop, but used them to tell very different stories, and it inspired him to develop a new style and create a story that was more personal; A CONTRACT WITH GOD.

After retiring THE SPIRIT, he largely abandoned comics for design work until the 70s, much of his work ignored even while his techniques became part of the language of comics. The generation of underground cartoonists who emerged in the sixties and seventies had absorbed the vocabulary that Eisner helped to develop, but used them to tell very different stories, and it inspired him to develop a new style and create a story that was more personal; A CONTRACT WITH GOD.

The book consists of four stories about 1930s Bronx tenement dwellers on the fictional Dropsie Avenue. In the title story, Frimme Hersh is sent to America by the townsfolk of his home in Russia in the late 19th. Before leaving, he draws up a contract with God, committing to His service. With the death of his adopted daughter, he abandons the contract. Eisner had lost his own daughter to cancer less than a decade before, and the emotion is still raw in his work. Hersh goes on to great success, but finds only emptiness in his life, and is led back to his old Synagogue and a new contract with God.

Eisner was part of a movement in American culture, the Jewish writer. After World War II, a number of writers emerged such as Saul Bellow, Philip Roth and Cynthia Ozick, who sought to examine Jewish identity in America, the clash of tradition and modernism, and the response to anti-Semitism. These writers refused to sentimentalise their communities, and contributed to the acceptance and assimilation of Jewish identity into mainstream American culture.

Eisner came to this tradition relatively late in life, not until his graphic novel phase, but it perhaps wasn't until then that the medium he had helped develop had come to a point where such work could be accepted. With a few pointed and purposeful exceptions, Eisner's stories deal with Jewishness and Judaism in ways that never resorted to stereotyping or crude caricature, but they are American stories and humanist tales as well.

'Eisner was part of a movement in American culture, the Jewish writer.' Eisner's voice sounds so unusual for comics, his sensibility and visual style a unique synthesis of influences, but in terms of being a storyteller, his voice was very much a part of American literature, and years from now, when graphic literature has a firmer foothold in the literary mainstream I believe that he will be remembered as just a significant part of this 20th century movement, just as he's regarded as one of the great comics innovators.

There had been Jewish American writers before, of course, but it was in the emergence of so many prominent writers at one time that the Jewish story could come to be seen as an American story. The opening salvo of this movement, indeed the first great post-war novel, was written by Saul Bellow who began THE ADVENTURES OF AUGIE MARCH:

"I am an American, Chicago born - Chicago, that somber city - and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted; sometimes an innocent knock, sometimes a not so innocent. But a man's character is his fate, says Heraclitus, and in the end there isn't any way to disguise the nature of the knocks by acoustical work on the door or gloving the knuckles."

Eisner was born in New York, not Chicago, but like March he was a man who made his own way, establishing a career unique in comics and a style that was recognisable wherever it was printed. I was stunned learn that he lived in Florida at the time of his death, because I associate him so strongly with the rain-slicked streets of the Bronx. His work was about New York and family, God and morality, and, yes, about Jewishness.

In FAGIN THE JEW, Eisner spins a tale of the character from Dickens' OLIVER TWIST, exploring the Jewish experience in nineteenth century England, and reclaiming and reinventing the character. His forthcoming final book THE PLOT is about how the Russian secret police created The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the nineteenth century, and how even though the book has been proved to be a fake for over a century, it has been used as 'evidence' by every anti-Semite from Hitler on down to support their racist ideologies.

I've been anticipating the book nervously since it was announced, excited for what it could be and nervous because it's such a monumental task. Eisner had described it as his most important book. His and his parents' generations had lived in the shadow of anti-Semitism for so many years that at the end of his life, when he saw it on the rise again, he sought to educate people about what had happened and what it meant.

People keep searching for someone to compare him to, often from the world of film, because it's another relatively young medium with a tendency to chew up and spit out its talent. There isn't a fair comparison to make, because few directors were able to bridge the changes from shorts to features, silents to talkies, and to continue being so productive for so long.

People keep searching for someone to compare him to, often from the world of film, because it's another relatively young medium with a tendency to chew up and spit out its talent. There isn't a fair comparison to make, because few directors were able to bridge the changes from shorts to features, silents to talkies, and to continue being so productive for so long.

Maybe John Ford or Ingmar Bergman or Manoelo de Oliveira, but even then, the comparison doesn't quite hold. It took decades for the innovations that Eisner wielded so masterfully in the 40s and 50s to become commonplace, and his recent work was about abandoning the stylistic conceits of his youthful efforts and instead developing a style so simple and transparent that it would be possible to hold the page up and, through it, to see the world.

At a time when graphic novels are becoming more popular and widely accepted, Eisner still seems to have been consigned to the background, despite his showcase at the Whitney Museum's 1996 "NYNY: City of Ambition" show and his 2002 Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Federation for Jewish Culture. He's as underappreciated by modern comic audiences as by the general public, despite a large and devout group of admirers and creators who rightly regard him as a legend.

At the close of Bellow's AUGIE MARCH the title character remarks, "I may well be a flop at this line of endeavor. Columbus too thought he was a flop, probably, when they sent him back in chains. Which didn't prove there was no America".

Eisner didn't get the widespread appreciation he deserved, but his efforts to establish comics as a literary form were not in vain. He lived long enough to see the release of books like PERSEPOLIS, JIMMY CORRIGAN, PALESTINE, and many others. I just hope there was a point, after finishing one of the many books of the past few years, where he allowed himself to lean back in his chair, to smile, and to think, "Well, it's a good start".

Eisner died on old man, but still at the top of his game. When people mention the Bronx, I don't think of the Yankees; I think of an Eisner sketch of a rain-drenched Dropsie Avenue, just another street in an immortal New York City that never was and always will be.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.