>> The Friday Review: Seven Peaches/Charger

>> Like Clockwork: An interview with Jane Irwin

More...

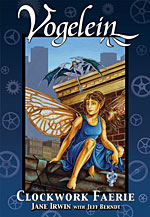

When it first previewed in the back of KINGS AND THIEVES #36 in 2001, VÖGELEIN (pronounced "Pfeu-gul-ine") had been four years in the making. Originally conceived in 1997 by Jane Irwin and Jeff Berndt as one short in a collection of stories, the VÖGELEIN idea, as Irwin notes in issue one, "began to grow in earnest and soon outpaced, and finally buried the rest of the ideas". The co-creators toyed with the idea of an illustrated fantasy novel that would have preceded Gaiman's STARDUST, but eventually decided on a comic book that Berndt would write and Irwin illustrate.

But even with a clear focus, the project had difficulty getting off the ground. After completing the draft of the first issue, Berndt hit a wall.

"He couldn't take it any further," Irwin recalls. "He was not happy with what he had written and he reached a point where he was not comfortable with the story."

In 1998, the two long-time collaborators came to an amicable parting, with Irwin retaining complete rights. Though she has been the sole creative force behind VÖGELEIN for over half a decade, Irwin is quick to credit Berndt's contribution: "I can't neglect how much of an effect he had on the original concept and on the original three issues."

That concept is nothing less than charming: VÖGELEIN (German for "little bird") is named for its protagonist, a clockwork fairy that must be wound every 36 hours to retain her identity, and her abilities to move and remember. When her "guardian" of 50 years dies, she must venture into a hostile city to find another. The captivating simplicity of the premise is deceptive: set against a delicately painted and exhaustively researched backdrop, and carefully layered with theme and character, this story is more than a mere "modern fairy tale".

VÖGELEIN has attracted fans the world over, as far north as Sweden and as far south as Australia; in places as disparate as Puerto Rico, Germany, and Ypsilanti, Michigan, the place where I first discovered it. Ypsilanti is a small post-industrial college town half an hour outside Detroit, where Irwin lived for nine years. She describes it as "caught in a perpetual cycle of rebirth and decay", the "redheaded stepchild" of its famous sister city, Ann Arbor. Having now moved to Ann Arbor, Irwin speaks from experience when she says, "Ypsi is the reason Ann Arbor doesn't have a bad side."

VÖGELEIN has attracted fans the world over, as far north as Sweden and as far south as Australia; in places as disparate as Puerto Rico, Germany, and Ypsilanti, Michigan, the place where I first discovered it. Ypsilanti is a small post-industrial college town half an hour outside Detroit, where Irwin lived for nine years. She describes it as "caught in a perpetual cycle of rebirth and decay", the "redheaded stepchild" of its famous sister city, Ann Arbor. Having now moved to Ann Arbor, Irwin speaks from experience when she says, "Ypsi is the reason Ann Arbor doesn't have a bad side."

For such a mean place, it plays a huge role in her work.

"I lived in Ypsilanti for nine years, there's no way it couldn't have had an effect on me. Talk about the sacred and the profane."

While she lauds praise upon local stores such as Cross Street Books ("a literal Delphic oracle of knowledge") where she did much of her primary research, and Art Attack, where she got much of her supplies, she doesn't gloss over the bad parts that were all too common to the city when she lived there.

"You have this filthy rag-tag bunch of bars that are opened and closed on an almost weekly basis, and liquor stores with cardboard for windows where people have robbed them and shot out the windows. It's just this amazing mix of really beautiful and downright scary stuff. I don't think you can live in a town like that for very long and not have it come across. A lot of that diamond-in-the-rough philosophy has carried into the book."

Much like Ypsilanti, the city that VÖGELEIN navigates is decaying and run down, something that Irwin's black and white painting vividly conveys. The griminess of the landscape is reflected in its inhabitants; Vogelein's nameless city is full of untrustworthy people, whether it be a lonely young man who hopes to possess her, or an actual Faerie of old who sees her as an abomination to be destroyed. If there is a diamond in this rough, it is the street sweeper Ezrael, a character important to Irwin as a negation of stereotypes.

"Part of the reason that I made Ezrael a male was because I wanted to avoid the 'bag-lady being street oracle' metaphor that you see quite a bit. And I also wanted a redemptive male character, because without a good solid male character at the end of the story you get the impression that all men are creeps. It was turning into a reversal of the whole virgin-whore conundrum. You had either this father figure, or these total jerks who she grows up and 'tries to date'. Just because I'm a woman, it's not my job to show that all men are evil or that only the female roles can be the strong and capable ones. That's not what I'm out to do."

"Part of the reason that I made Ezrael a male was because I wanted to avoid the 'bag-lady being street oracle' metaphor that you see quite a bit. And I also wanted a redemptive male character, because without a good solid male character at the end of the story you get the impression that all men are creeps. It was turning into a reversal of the whole virgin-whore conundrum. You had either this father figure, or these total jerks who she grows up and 'tries to date'. Just because I'm a woman, it's not my job to show that all men are evil or that only the female roles can be the strong and capable ones. That's not what I'm out to do."

The fair representation of gender is an issue important to Sequential Tart, the celebrated online journal and community that Irwin calls her "home base" on the web. While the website is known for its promotion of women's influence on comics as both creators and readers, Irwin is quick to point out that gender issues are trumped by a love of comics.

"It's fairly equal opportunity. It does have a strong focus on women in comics; however, its stronger focus is on good sequential art: open minded comics, comics that feature a variety of subjects, and most importantly comics that are more than just, forgive me, male adolescent power fantasy fulfilment. You know, guys in capes and tights hitting things."

However, like most American comics enthusiasts, fans and creators alike, "capes and tights" was exactly how she got into it.

"I subscribed to every X-book in the 80s. I subscribed to all three SPIDER-MAN books. I was a tomboy and I fit that demographic okay. But I remember the first time I read, first WATCHMEN, and then MAUS, and it was as though someone had just hit me over the head with a mallet, it was like opening up a whole new world. Reading that made me understand 'Wow, there's a heck of a lot more that I can do', and then I started getting into really independent really underground books, buying whatever I could get my hands on and seeing the vast range of stuff that you could get if you went into a comic store as opposed to just your drug store and picking up your weekly IRON MAN and SUPERMAN kind of things."

Just as Irwin is happy to see a transition away from superhero-exclusive comics, she is glad to see the industry become more equal opportunity.

"It's a transition period right now. Women get a lot more respect right now than they did 15 years ago," she says. "And I'm really happy to be part of pushing that forward. I am really looking forward to the day when it won't be an issue, when [the question] will just be, 'What's it like to be a comics creator?' Instead of, 'What's it like to be a female comics creator?'"

"It's a transition period right now. Women get a lot more respect right now than they did 15 years ago," she says. "And I'm really happy to be part of pushing that forward. I am really looking forward to the day when it won't be an issue, when [the question] will just be, 'What's it like to be a comics creator?' Instead of, 'What's it like to be a female comics creator?'"

Male or female, life is tough for the independent comics creator, especially one as methodical as Irwin. Each page of VÖGELEIN can take her up to 24 hours or more to paint.

"Each issue took me more than six months to complete. I allowed the work to backlog so that I had four complete issues before I even started publishing. So that allowed, while it was publishing bi-monthly, it allowed me eight months to get issue five done and together and published."

Also time consuming is the necessary research into horology, history, Gypsy and German culture, and faerie folklore that make the story so believable. She has a crew of "expert" friends that she consults for questions about the "feasibility" of VÖGELEIN's machinations. For the Irish, she goes back to Lady Gregory's original collections of oral Irish folklore, a source so old that William Butler Yeats also used it.

"Something that's masquerading as historical fiction isn't good enough for me," she says of the work of others. She applies equally rigorous standards to herself: "I want to tear things back as far as I can to the source without having to actually learn Irish Gaelic."

She does all this in addition to holding a full time job as a web designer. While she is currently busy promoting the book, Irwin doesn't have time to work on a new issue. She's not painting, she's not even writing, though there are plans to get back at it with the fall convention season now behind her. "This winter I hope to write probably three or four scripts. If I can get them all out of my head."

All though VÖGELEIN was originally published in individual issues, Irwin finds this approach too costly. She calls the original run of VÖGELEIN an "incredibly expensive flier campaign" for the collected volume that is now available in stores. The next volume in the VÖGELEIN saga will be released in a similar format. She hopes to deal exclusively in bound graphic novels from here on out.

Given the painstaking work that Irwin puts into VÖGELEIN, it'll probably be a while before the next entry in the story is released, but the quality of Irwin's work has won her a dedicated fan base who will likely be ready and waiting when the time comes.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.